I've been listening to John Lennon's "Happy Xmas (War is Over)" and "Imagine" on repeat for the last couple of days. It was, after all, 29 years ago today that Lennon was murdered outside his New York apartment - a day I still have trouble coming to grips with, though it happened five years before I was born.

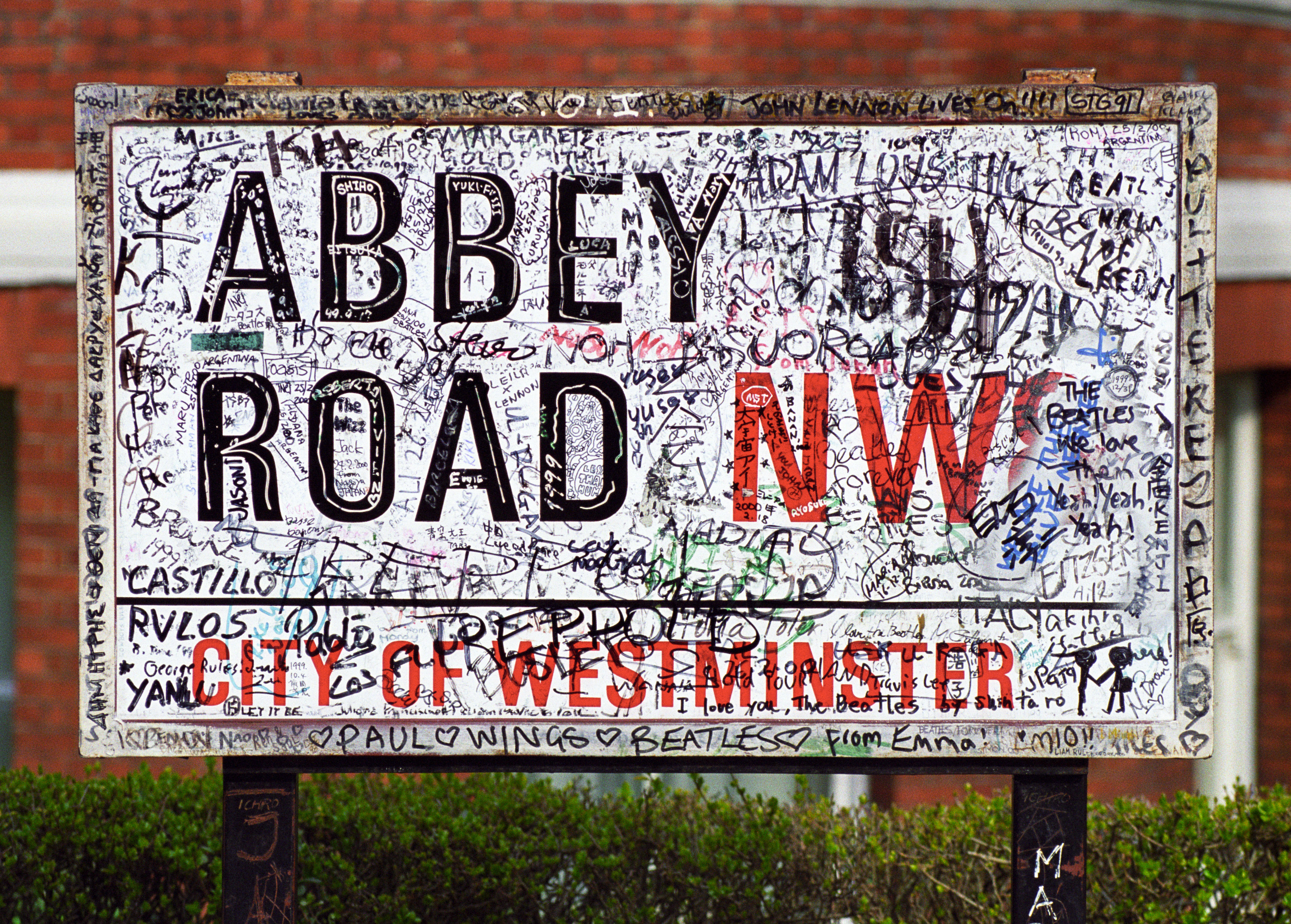

Imagine a life without the Beatles - it's not something I'd like to do. I got my first CD on my 10th birthday - it was the Beatles Anthology 2. That was the end of my life not knowing the Beatles, though John had been dead for 15 years already. At my 5th grade talent show, while other kids danced to Ace of Base and "This is How We Do It," three friends and I did Sgt. Pepper (I was Paul). Soon, I'd discovered my dad's old Beatles vinyls; growing up in an era when rock music was the symbol of rebellion, he probably never expected that he'd be able to share the same music as his son. Twenty years from now, when the mass public has finally expunged "Party in the USA" and autotune from its collective memory, my own kids will still be asking me who the Walrus was, and debating whether Revolver is better than Abbey Road.

I can't describe what makes the Beatles' music so great, ingrained as it is almost into my identity - thankfully, there are plenty who can do so better than I can.

Nor can I add anything new to the tomes explaining how the Beatles' greatness transcended their music. They'll be forever linked with the optimism and descent into heartache of the 60s - and in many ways, they follow the arc of the Baby Boomer generation, with Lennon as its prophet.

Nor can I add anything new to the tomes explaining how the Beatles' greatness transcended their music. They'll be forever linked with the optimism and descent into heartache of the 60s - and in many ways, they follow the arc of the Baby Boomer generation, with Lennon as its prophet. In the Beatles were captured the essence of youth: both its dynamic energy and passionate frustration with existing order. Paul embodied its boyish yearning: the thrill of love, the anxiety and anger of heartache. He was perfectly balanced by John's somewhat darker tendencies, and even greater ambition to experiment and push the bounds of what was known. Though less given to Paul's romantic tendencies, John dreamed no less about love; for him, it was a revolution - not just individualistic love in the romantic sense, but a love for all mankind that recognized our connectedness beyond individual interest. Indeed, the Beatles established popular music as something which was more than something to nod your head and shake your hips to, but as an emotional force which could cause you to think and dream about the world differently.

Above all, the Beatles represented a willingness to imagine. With youthful inexperience came the freedom not to be constrained by knowledge of what hasn't worked in the past. They didn't wait for experience, but took on the world in their 20s. And they urged others to do the same, regardless of what world leaders' experience told them was "realistic" to hope for. What else from a band who was rejected by their first label audition with the words, "Guitar groups are on the way out"? The executive's "experience," likely driven by marketing data, resulted in the worst blunder in the music business's history.

Above all, the Beatles represented a willingness to imagine. With youthful inexperience came the freedom not to be constrained by knowledge of what hasn't worked in the past. They didn't wait for experience, but took on the world in their 20s. And they urged others to do the same, regardless of what world leaders' experience told them was "realistic" to hope for. What else from a band who was rejected by their first label audition with the words, "Guitar groups are on the way out"? The executive's "experience," likely driven by marketing data, resulted in the worst blunder in the music business's history.But as the 60s wound down, the dream began to crumble. The Beatles' own troubles with each other mirrored the global turmoil of 1968-69: an escalating war, violent protests in Chicago, and the election of Richard Nixon on the promise of a return to "law and order." As the United States seemed to spiral out of control, driven by the restlessness of a Boomer generation at the height of its energetic anxiety, so too did the Beatles. Though their music continued to peak, their personal relationships deteriorated. Until finally, in 1970, they broke up, turning the final page of the last decade. As if youthful energy had rent itself apart.

In the 70s, as the United States wrestled with its identity between the passion of idealism and the security of paycheck, home, and order, Lennon and McCartney similarly drifted apart. While both continued to churn out top-notch music for several years (Lennon more so), Lennon eventually retreated from his creative work for a five year househusband hiatus, while McCartney contented himself writing silly love songs. And just as Lennon was about to return to public life to launch a new album, even seeming close to reconciling with McCartney, Mark David Chapman snuffed it all out with five shots in Lennon's back.

So John Lennon's murder wasn't just when the music died, as Time's cover put it at the time - Chapman's bullets also finished off the era of youthful idealism over aged realism, of love over lust for gain, of widespread yearning for something more to life than a secure march to retirement. After all, Ronald Reagan was elected just one month before Lennon's assassination. Together, the two events sealed off a shift in America's vision for itself - from one which sought a brotherhood of Man, to one which equated lofty liberty with an atomized pursuit of material gain for oneself and immediate family unit.

I feel that yearning for meaning over materialism, for connectedness over the isolation of unfettered individualism, in my own generation. And we've got our own issues that will put those values to the test.

This week, the world's leaders in Copenhagen will have to decide whether narrow self- and national-interest outweigh the shared interests of the brotherhood of Man. They may despair that current realities make it impossible to meet climate targets, and fail to seize the opportunity. If leaders think that, they should remember a Decca Records executive who saw the "reality" that "guitar groups are on the way out," and missed the opportunity to sign the most successful musical group of all time.

This week, the world's leaders in Copenhagen will have to decide whether narrow self- and national-interest outweigh the shared interests of the brotherhood of Man. They may despair that current realities make it impossible to meet climate targets, and fail to seize the opportunity. If leaders think that, they should remember a Decca Records executive who saw the "reality" that "guitar groups are on the way out," and missed the opportunity to sign the most successful musical group of all time.

In my life, I'll never see the Beatles reunite to perform together. But I can imagine. And I can imagine a future that's different from today's. I can imagine a world where we place greater value on the priceless than on the output of factories; where we act not out of a sense of what hasn't worked before, but out of hopeful urgency for what must now be done. And I'm not the only one.

No comments:

Post a Comment